文字难度:★★★☆

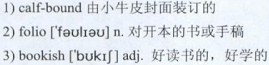

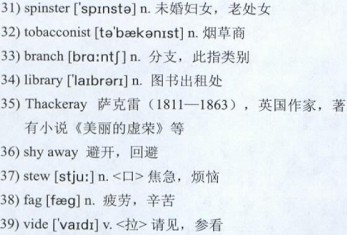

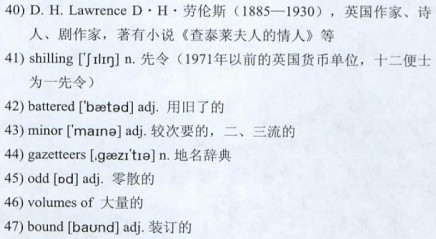

When I worked in a second-hand bookshop—so easily pictured, if you don’t work in one, as a kind of paradise where charming old gentlemen browse eternally among 1)calf-bound 2)folios—the thing that chiefly struck me was the rarity of really 3)bookish people. Our shop had an exceptionally interesting stock, yet I doubt whether ten per cent of our customers knew a good book from a bad one. First edition 4)snobs were much commoner than lovers of literature, but oriental students 5)haggling over cheap textbooks were commoner still, and vague-minded women looking for birthday presents for their nephews were commonest of all.

没在旧书店做过事的人,很容易把这种地方想象得和天堂一样,永远有气度儒雅的老先生徜徉在书架面前,翻阅着小牛皮封面的典籍;然而就我在一家旧书店的工作经历而言,印象最深的却是:真正的读书人可谓凤毛麟角。我们那家店的书都异常有趣,但我怀疑能从其中挑出孰好孰坏的顾客不知有没有十分之一。店里最常见的顾客得算那些来给子侄们挑选生日礼物的迷糊的女士们;其次就是来买教科书的东方留学生,他们只知道没完没了地讨价还价;至于说文学爱好者,则还没有专买初版书的附庸风雅之辈来得多。

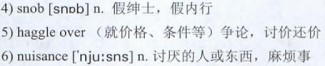

Many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a 6)nuisance anywhere, but have special opportunities in a bookshop. For example, the dear old lady who “wants a book for an 7)invalid” (a very common demand, that), and the other dear old lady who read such a nice book in 1897 and wonders whether you can find her a copy. Unfortunately she doesn’t remember the title or the author’s name or what the book was about, but she does remember that it had a red cover. But apart from these there are two well-known types of 8)pest by whom every second-hand bookshop is9)haunted: One is the 10)decayed person smelling of old bread 11)crusts who comes every day, sometimes several times a day, and tries to sell you worthless books. The other is the person who orders large quantities of books for which he has not the smallest intention of paying. In our shop we sold nothing on credit, but we would put books aside, or order them if necessary, for people who arranged to fetch them away later. Scarcely half the people who ordered books from us ever came back. It used to puzzle me at first. What made them do it? They would come in and demand some rare and expensive book, would make us promise over and over again to keep it for them, and then would vanish never to return. But many of them, of course, were unmistakable 12)paranoiacs. They used to talk in a 13)grandiose manner about themselves and tell the most 14)ingenious stories to explain how they had happened to come out of doors without any money—stories which, in many cases, I am sure they themselves believed. In a town like London there are always plenty of not-quite-15)certifiable 16)lunatics walking the streets, and they tend to 17)gravitate towards bookshops, because a bookshop is one of the few places where you can hang about for a long time without spending any money. In the end, one gets to know these people almost at a glance. For all their big talk there is something 18)moth-eaten and aimless about them. Very often, when we were dealing with an obvious paranoiac, we would put aside the books he asked for and then put them back on the shelves the moment he had gone. None of them, I noticed, ever attempted to take books away without paying for them—merely to order them was enough. It gave them, I suppose, the illusion that they were spending real money.

Many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a 6)nuisance anywhere, but have special opportunities in a bookshop. For example, the dear old lady who “wants a book for an 7)invalid” (a very common demand, that), and the other dear old lady who read such a nice book in 1897 and wonders whether you can find her a copy. Unfortunately she doesn’t remember the title or the author’s name or what the book was about, but she does remember that it had a red cover. But apart from these there are two well-known types of 8)pest by whom every second-hand bookshop is9)haunted: One is the 10)decayed person smelling of old bread 11)crusts who comes every day, sometimes several times a day, and tries to sell you worthless books. The other is the person who orders large quantities of books for which he has not the smallest intention of paying. In our shop we sold nothing on credit, but we would put books aside, or order them if necessary, for people who arranged to fetch them away later. Scarcely half the people who ordered books from us ever came back. It used to puzzle me at first. What made them do it? They would come in and demand some rare and expensive book, would make us promise over and over again to keep it for them, and then would vanish never to return. But many of them, of course, were unmistakable 12)paranoiacs. They used to talk in a 13)grandiose manner about themselves and tell the most 14)ingenious stories to explain how they had happened to come out of doors without any money—stories which, in many cases, I am sure they themselves believed. In a town like London there are always plenty of not-quite-15)certifiable 16)lunatics walking the streets, and they tend to 17)gravitate towards bookshops, because a bookshop is one of the few places where you can hang about for a long time without spending any money. In the end, one gets to know these people almost at a glance. For all their big talk there is something 18)moth-eaten and aimless about them. Very often, when we were dealing with an obvious paranoiac, we would put aside the books he asked for and then put them back on the shelves the moment he had gone. None of them, I noticed, ever attempted to take books away without paying for them—merely to order them was enough. It gave them, I suppose, the illusion that they were spending real money.

我们的大部分主顾恐怕去哪里买东西都不会招人喜欢,但只要踏进书店,他们倒能享受“上帝”的待遇。比如说,某位可亲的老妇人“想买本书送给一位缠绵病塌的人看”(实在常见的一个要求);又一位可爱的老妇人说她1897年看过一本不错的书,问你能不能帮她找找,糟糕的是,她既不记得书名,也不记得作者姓甚名谁,更说不清书里讲了些什么,她就记得那本书的封皮是红色的。这还不算什么,还有两种人更讨嫌,成天如孤魂野鬼般盘桓在每一家旧书店,人见人厌。一种是每天都会光顾、有时一天来几次的穷困潦倒之人,浑身散发着一股隔夜面包皮才有的味儿,缠着你买下他那些一文不值的破书。另一种人会向你预订一大堆书,但却从来没有一丁点儿掏钱的打算。我们店里从不赊账,不过顾客看中的书要是一时不方便带走,我们也可以为他保存起来,必要的话替他预订,待他日后来取。然而真正回来取走预订书籍的顾客,就我们店里的情况看来,不到一半。起初这让我颇有些疑惑不解:是什么原因让他们这么做呢?他们走进来,询问有没有某本罕见而价格不菲的书籍,再三要求我们答应为他们保留那书,之后便消失了,永远不再踏进这书店。不过最后我明白了,这种人大部分是不折不扣的妄想狂。他们惯常于为自己说些冠冕堂皇的话,编造出种种精彩绝伦的故事,说自己如何凑巧出门没带钱,我敢肯定,大多数情况下,他们自己都对这样的故事信以为真了。在伦敦这样的城市里,总是有大量无法被确切诊断患有精神病的人在街头游荡,这些人往往爱到书店里来,因为书店是少数几个可以逗留很长时间而又用不着花费半个子儿的地方之一。到最后你几乎只消瞥一眼就能认出这种人。尽管他们大话连篇,但他们所说的大多是一些陈旧过时而又无伤大雅的事情。对待这类显而易见的妄想狂,我们通常是当面把他指定的书单独放起来,他一离开便立马放回到书架上。我注意到,这些人从来没有不付钱就把书带走的企图,仅仅是预订一下,他们就满足了——我猜,这能带给他们一种自己在花真金白银买东西的幻觉。

Like most second-hand bookshops we had various 19)sidelines. We sold second-hand typewriters, for instance, and also stamps—used stamps, I mean. But our principal sideline was a 20)lending library—the usual “two penny no-21)deposit” library of five or six hundred volumes, all fiction.

Like most second-hand bookshops we had various 19)sidelines. We sold second-hand typewriters, for instance, and also stamps—used stamps, I mean. But our principal sideline was a 20)lending library—the usual “two penny no-21)deposit” library of five or six hundred volumes, all fiction.

和大多数旧书店一样,我们店里也兼售一些其他商品。比如,我们出售二手打字机,也卖邮票——我指的是用过的邮票。不过,我们的主要兼营业务是图书租赁——“两便士租一本,免押金”,书目大概五六百种,全都是小说类。

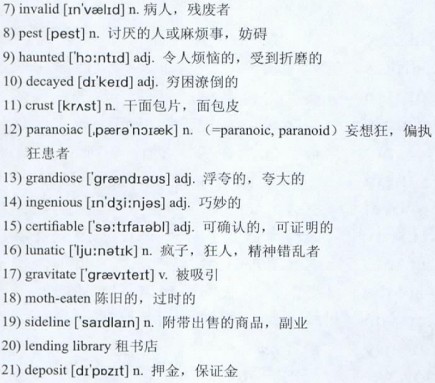

Our shop stood exactly on the frontier between 22)Hampstead and 23)Camden Town, and we were 24)frequented by all types, from 25)baronets to bus-conductors. Probably our library subscribers were a fair 26)cross-section of London’s reading public. It is therefore worth noting that of all the authors in our library the one who “went out” the best was—Hemingway? 27)Walpole? No, 28)Ethel M. Dell, with 29)Warwick Deeping a good second and 30)Jeffrey Farnol, I should say, third. Dell’s novels, of course, are read solely by women, but by women of all kinds and ages and not, as one might expect, merely by wistful 31)spinsters and the fat wives of 32)tobacconists. It is not true that men don’t read novels, but it is true that there are whole 33)branches of fiction that they avoid. Men read either the novels it is possible to respect, or detective stories. But their consumption of detective stories is terrific. One of our subscribers, to my knowledge, read four or five detective stories every week for over a year, besides others which he got from another 34)library. What chiefly surprised me was that he never read the same book twice. He took no notice of titles or author’s names, but he could tell by merely glancing into a book whether he had “had it already.”

我们书店正好开在汉普斯特德和卡姆登陶恩两个城区的交界处,经常来租书的顾客上至准男爵,下至公车售票员,形形色色,什么人都有。这些来租书的人可谓是伦敦阅读人群的一个缩影。因而值得留意的是,在我们租书处最受追捧的是谁的作品呢?既不是海明威,也不是沃波尔,而是爱塞 尔·M·黛尔,其次是沃里克·狄平,排在第三位的,大概就是杰弗里·法诺了。黛尔的小说当然只有女性才会捧读,但千万不要以为她的读者只是些愁苦的老姑娘或者卷烟店的胖老板娘,实际上其女性读者形形色色,且年纪长幼不一而足。若说男人不看小说那倒也不尽然,但男人们的确不怎么看某些类型的小说。男性看的都是有可能在交谈时成为炫耀资本的小说,再有就是侦探小说。不过,他们阅读的侦探小说的数量大得吓人。我记得我们店有位常客,有一年多的时间里,他每个星期要看四到五本侦探小说,这还不算他在另一家书店看过的。最让我吃惊的是,同一本小说他从来不会看第二遍。他根本不去留意书名或者作者是谁,但只要翻开哪本书随便扫一眼,他就能告诉你这本书他是不是“已经看过了”。

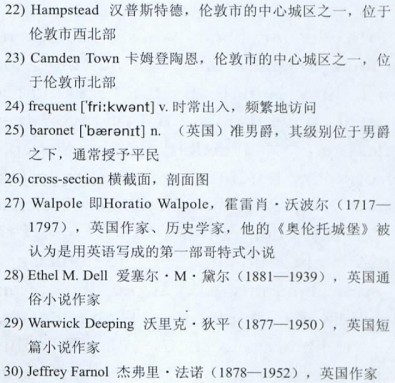

In a lending library you see people’s real tastes, not their pretended ones, and one thing that strikes you is how completely the “classical” English novelists have dropped out of favor. It is simply useless to put 35)Thackeray, Jane Austen, etc. into the ordinary lending library; nobody takes them out. At the mere sight of a nineteenth-century novel people say, “Oh, but that’s old!” and 36)shy away immediately. And another—the publishers get into a 37)stew about this every two or three years—is the unpopularity of short stories. The kind of person who asks the librarian to choose a book for him nearly always starts by saying “I don’t want short stories,” or “I do not desire little stories,” as a German customer of ours used to put it. If you ask them why, they sometimes explain that it is too much 38)fag to get used to a new set of characters with every story; they like to “get into” a novel which demands no further thought after the first chapter. I believe, though, that the writers are more to blame here than the readers. The short stories which are stories are popular enough, 39)vide 40)D. H. Lawrence, whose short stories are as popular as his novels.

在租书店,你可以看到人们真实的阅读品味,而不是他们假装出来的那一套,你会赫然发现,原来英国的“古典”小说家们已经彻底失宠了。你根本毋需将萨克雷、简·奥斯汀这些人的作品摆上租书柜台,即便摆了也租不出去。人们瞟见这些19世纪的著作就会说:“哇,这书好老!”说完便跳过这本去看下一本。另外,短篇小说也不甚受落,出版商们每两三年就得为此发一阵子愁。有些来租书的顾客总是让我们帮他选书,但几乎总是一开口就在强调“别给我拿短篇小说”,或者“我对小故事没兴趣”,一个常在我们店里租书的德国人就是这样。如果你去问他们为什么,或许有人就会告诉你:每读一个小故事都要重新认识一大群人物很麻烦,他们喜欢看篇幅长一点的小说,因为只要看过开头一章,后面就不用再费心去弄清谁是谁了。我倒觉得这种现象也不能全怨读者,作者自身的原因恐怕更多一些。真正称得上是小说的短篇小说始终是深受欢迎的,就拿D·H·劳伦斯来说,他的短篇小说就和他的长篇小说一样口碑甚好。

…

There was a time when I really did love books—loved the sight and smell and feel of them, I mean, at least if they were fifty or more years old. Nothing pleased me quite so much as to buy a pile of them for a 41)shilling at a country auction. There is a peculiar flavor about the 42)battered unexpected books you pick up in that kind of collection: 43)minor eighteenth-century poets, out-of-date 44)gazetteers, 45)odd 46)volumes of forgotten novels, 47)bound numbers of ladies’ magazines of the sixties…

曾经有段时间我确实非常爱书——我热爱书页在手中摩挲时书香隐隐袭来的那种感觉,当然,我说的是至少五十年甚至更古老的书。再也没有比在乡村拍卖会上花一个先令买回一大堆这种书更让我开心的事了。这些不期而遇随你挑选的旧书有一种奇异的味道:你在这里能找到18世纪名不见经传的诗人们的作品、过时的地名辞典、大量零散的早已被遗忘的小说,以及19世纪60年代女士杂志的合订本……