当读到妈妈们总喜欢念叨女儿们的“头发”时,我不禁笑了起来。真的,妈妈好喜欢念叨我的头发,还有我的衣着。也许就像作者说的那样,在这个世界上,女儿在某种程度上代表了妈妈,所以妈妈们总希望女儿们能像她们所希望的那样装扮和生活。

我知道妈妈很爱我,她喜欢别人说我和她长得很像,喜欢细看我的手指,说着,和妈妈年轻时的手指一模一样。呵呵,我是妈妈的影子。但她终于也理解了,她的想法代表了她所成长的那个年代,比如,婚姻对女人的重要性。女儿长大了,有自己想要选择的生活,有自己想要走的路。

如果说小时候很乖但还是会有一点点的叛逆,那么现在更多的是理解。

妈妈,我长大了,但我没有飞离你。

妈妈,谢谢你!我爱你!我永远都是你的贴心小棉袄!^_^

文字难度:★★★☆

The five years I recently spent researching and writing a book about mothers and daughters also turned out to be the last years of my mother’s life. In her late eighties and early nineties, she gradually weakened, and I spent more time with her, caring for her more intimately than I ever had before. This experience—together with her death before I finished writing—transformed my thinking about mother-daughter relationships.

最近五年,我把时间都花在研究并撰写一本关于母亲和女儿的书上,这五年刚好也是我母亲生命中的最后岁月。从她年近九旬到九十多岁这几年里,她的身体日渐虚弱,我花了更多时间和她待在一起,并前所未有地悉心照料她。这种体验——以及在我写完此书前她的离世——改变了我对母女关系的想法。

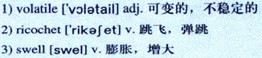

All along I had in mind the questions a journalist had asked during an interview about my research. “What is it about mothers and daughters?” she blurted out. “Why are our conversations so complicated, our relationships so tense?” These questions became more urgent and more personal, as I asked myself: What had made my relationship with my mother so 1)volatile? Why had I often 2)ricocheted between extremes of love and anger? And what had made it possible for my love to 3)swell, and my anger to dissipate in the last years of her life?

All along I had in mind the questions a journalist had asked during an interview about my research. “What is it about mothers and daughters?” she blurted out. “Why are our conversations so complicated, our relationships so tense?” These questions became more urgent and more personal, as I asked myself: What had made my relationship with my mother so 1)volatile? Why had I often 2)ricocheted between extremes of love and anger? And what had made it possible for my love to 3)swell, and my anger to dissipate in the last years of her life?

我一直对有个记者就我的研究进行采访时提出的问题念念不忘。“母亲和女儿之间究竟是怎么回事?”她脱口而出,“为什么我们的对话总是那么复杂,我们的关系总是那么紧张?”当我自问:是什么让我和母亲的关系这么飘忽多变?为什么我的感情总是在爱与怒这两个极端之间波动?在母亲生命里的最后那几年,是什么让我的爱意增长,愤怒消散?这些问题变得更加紧迫且与我个人相关。

During the research, I discover that there is a special intensity to the mother-daughter relationship, because talk—particularly about personal topics—plays a larger and more complex role in girls’ and women’s social lives than in boys’ and men’s. For the ladies, talk is the glue that holds a relationship together—and the explosive that can blow it apart.

在研究期间,我发现母女关系中有一个特殊的焦点,因为比起男孩和男人,交谈——尤其是关于私人话题的交谈——在女孩和女人的社会生活中作用更大、更复杂。对于女性来说,交谈是维持彼此关系的黏合剂,也是让双方关系破裂的炸药。

Daughters often object to remarks that seem harmless to outsiders, like this one, described by a student of mine, Kathryn Ann Harrison:

女儿们经常会反驳那些在局外人看来似乎毫无伤害性的评论,像我的学生凯思琳·安·哈里森描述的这种:

“Are you going to quarter those tomatoes?” her mother asked, as Kathryn was preparing a salad. Stiffening, Kathryn replied, “Well, I was. Is that wrong?”

“你要把那些西红柿切成四瓣吗?”当凯思琳在做沙拉时,她母亲问道。凯思琳硬邦邦地回答道:“嗯,本来是。错了吗?”

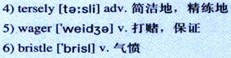

“No, no,” her mother replied. “It’s just that personally, I would slice them.” Kathryn said 4)tersely, “Fine.” But as she sliced the tomatoes, she thought, can’t I do anything without my mother letting me know she thinks I should do it some other way?

“不,不。”她母亲回答道,“只是个人习惯问题,我会把它们切成片。”凯思琳斩钉截铁地说:“好吧。”但当她把西红柿切片时,她心想,难道我就不能不按照母亲告诉我的另一种方法来做一些事吗?

I’m willing to 5)wager that Kathryn’s mother thought she had merely asked a question about a tomato. But Kathryn 6)bristled, because she heard the implication, “You don’t know what you’re doing. I know better.”

我愿意打赌,凯思琳的母亲认为她只是问了一个关于西红柿的问题而已。但凯思琳生气了,因为她听出了其中的暗示——“你不熟悉自己正在做的事。我比你更清楚该怎样做。”

I interviewed dozens of women of varied geographic, racial and cultural backgrounds. The complaint I heard most often from daughters was, “My mother is always criticizing me.” The corresponding complaint from mothers was, “I can’t open my mouth. She takes everything as criticism.”

我采访了几十个不同地区、不同种族和不同文化背景的女人。我从女儿们那里听得最多的抱怨是,“我妈永远在批评我。”而母亲们相应的抱怨则是,“我不能开口。她把我说的一切都当成批评。”

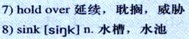

I know it is because a mother’s opinion matters so much, that she has enormous power. Her smallest comment—or no comment at all, just a look—can fill a daughter with hurt, and consequently, anger. But I learned that mothers who have spent decades watching out for their children, often persist in commenting, because they can’t get their adult children to do what is ( in their belief ) obviously right. Where the daughter sees power, the mother feels powerless. The power that mothers and daughters 7)hold over each other derives, in part, from their closeness.

我知道,那是因为女儿对于母亲的意见看得很重,以至于母亲有很大的权力。她最微小的评论——或者根本不是评论,仅仅是一个眼神——都能给女儿带来伤害,因而使女儿感到愤怒。但我发现,那些几十年来密切关注子女的母亲通常会坚持作出评论,因为她们不能使成年子女去做那些(她们坚信是)明显正确的事情。当女儿看到自己的力量时,母亲却感到自己毫无权力。这种母女之间互相制约的权力,部分来源于她们的亲密。

On the other hand, mothers and daughters search for themselves in the other, as if hunting for treasure, as if trying to find the sameness, which affirms who they are. This can be pleasant: After her mother’s death, one woman noticed that she wipes down the 8)sink, cuts an onion and holds a knife just as her mother used to do. She found this comforting, because it meant that, in a way, her mother was still with her.

另一方面,母亲和女儿会在对方身上寻找自己的影子,彷佛在寻找财富,彷佛努力在对方身上寻找共同点,从而确定她们自己是谁。这个过程可能是令人愉快的:有个女人在母亲去世后发现自己洗水池、切洋葱乃至拿刀的姿势和母亲生前的姿势一样。她从中得到了安慰,因为这在某种程度上意味着,她的母亲仍然和她在一起。

When visiting my parents a few years ago, I was sitting across from my mother, when she asked, “Do you like your hair long?”

几年前,我去看望我的父母,当我坐在我母亲对面时,她问道:“你喜欢你的长头发吗?”

I laughed, and she asked what was funny. I explained that in my research, I had come across many examples of mothers who criticize their daughters’ hair. “I wasn’t criticizing,” she said, looking hurt. I asked, “Mom, what do you think of my hair?” Without hesitation, she said, “I think it’s a little too long.”

我笑了起来,她问我有什么好笑的。我解释道,在我的研究中,我碰见过很多关于母亲批评女儿发型的例子。“我不是在批评。”她说,一脸受伤害的样子。我问:“妈妈,你觉得我的发型怎样?”她毫不犹豫地回答道:“我觉得太长了。”

Hair is one of what I call “The Big Three”, that mothers and daughters critique (the other two are clothing and weight). Mothers always feel entitled, if not obligated, to say that, “I think you’d look better if you got your hair out of your eyes,” knowing that mothers are judged by their daughters’ appearance, because daughters represent their mothers to the world.

头发是被我称为母亲和女儿会相互批判的“三大问题”之一(另外两个问题是衣着和体重)。母亲总觉得自己有权利(如果不是有义务)说,“我觉得如果你把头发从眼睛上拨开,会更好看一些。”母亲知道,大家会以女儿的相貌来评价母亲,因为在世人的眼里,女儿是母亲的代表。

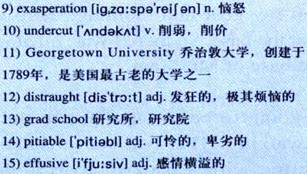

But daughters want their mothers to see and value what they value in themselves; that’s why a question that would be harmless in one context can be hurtful in another. For example, a woman said that she told her mother of a successful presentation she had made, and her mother asked, “What did you wear?” The woman exclaimed, in 9)exasperation, “Who cares what I wore?!” In fact, the woman cared. She had given a lot of thought to selecting the right outfit. But her mother’s focus on clothing—rather than the content of her talk—seemed to 10)undercut her professional achievement.

但女儿希望母亲看到并重视她们自我重视的价值,这就是为什么一个在某个语境里没有伤害性的问题,在另一个语境里可以伤人。比如,有个女人说,她告诉母亲她的演说很成功,她母亲却问:“你那时穿什么衣服?”这个女人愤怒地惊呼,“有谁会在意我那时穿什么?!”事实上,她是在意的。她花了很多心思搭配服饰。但她母亲把注意力集中在她的穿着而不是她演讲的内容上,这似乎贬低了她的职业成就。

Then again, a mother may seem to devalue her daughter’s choices, simply because she doesn’t understand the life her daughter has chosen. I think that was the case with my mother and me.

然而,母亲看似贬低女儿的选择,可能仅仅是因为她不理解她女儿所选择的生活。我想我和我母亲的情况就是这样。

My mother visited me, shortly after I had taken a teaching position at 11)Georgetown University, and I was eager to show her my new home and new life. She had disapproved of me during my rebellious youth, and had been 12)distraught when my first marriage ended six years earlier. Now I was a professor! Clearly, I had turned out all right. I was sure she’d be proud of me—and she was. When I showed her my office, with my name on the door and my publications on the shelf, she seemed pleased and approving.

我在美国乔治敦大学获得教职不久,母亲来看望我。我渴望向她展示我的新家和新生活。我年轻时很叛逆,她当时是不认可的。6年前,我的第一段婚姻结束,她极其烦恼。如今我却当了教授!显然,我已经从逆境中挺了过来,生活得很好。我确信母亲一定会以我为荣——事实也的确如此。我带她参观我的办公室,门上写着我的名字,书架上摆着我的著作,她看上去很开心,很赞许。

Then she asked, “Do you think you would have accomplished all this if you had stayed married?” “Absolutely not,” I said. “If I’d stayed married, I wouldn’t have gone to 13)grad school to get my PhD.”

然后她问道:“你觉得如果你没有离婚,会不会有今天这样的成就?”“当然不会有。”我说,“如果我没有离婚,我就不会去读研究院,拿博士学位。”

“Well,” she replied, “if you’d stayed married you wouldn’t have had to.” Ouch. With her casual remark, my mother had reduced all I had accomplished to the consolation prize.

“可是,”她回答道,“如果你没有离婚,你就用不着去读书。”哎唷,她一句不经意的评论就把我获得的全部成就贬低为安慰奖。

But now I think she was simply reflecting the world she had grown up in, where there was the one and only one measure by which women were judged successful or 14)pitiable: marriage. She probably didn’t know what to make of my life, which was so different from any she could have imagined for herself.

但现在我认为,她的言论只不过反映了她成长的那个时代的观点,当时评判女人是成功还是可怜的唯一标准是婚姻。她不理解也不知道该如何对待我所选择的人生,那和她可以设想的人生是如此不同。

Years ago, I was surprised when my mother told me after I had sent her a letter beginning with the words, “Dearest Mom,”—that she had waited her whole life to hear me say that. I thought this a bit strange of her, until a young woman named Rachael sent me copies of e-mails she had received from her mother. In one, her mother responded to Rachael’s 15)effusive Mother’s Day card: “Oh, Rachael!!!!! That was so WONDERFUL!!! It almost made me cry. I’ve waited 25 years, 3 months and 7 days to hear something like that…”

几年前,我写了一封信给母亲,开头是“我最亲爱的妈妈”,母亲后来告诉我,她一生都在等我说这句话。我很惊讶,觉得这并不像她的作风,直到有个叫雷切尔的年轻女士转发给我一些她母亲寄给她的电子邮件,我才想通了。其中一封电邮是她母亲看了雷切尔写的感情横溢的母亲节贺卡后作出的答复:“噢,雷切尔!!!!!这真是太棒了!!!它几乎让我流泪。为了听到这样的话语,我已经等了25年零3个月又7天……”

小资料  乔治敦大学创建于1789年,是美国最古老的大学之一,也是美国首都华盛顿特区声誉最高的综合性私立大学。它位于首都华盛顿地区市中心,坐落在风景美丽如画的乔治城以及波多马克河边,距离白宫3200米左右。

乔治敦大学创建于1789年,是美国最古老的大学之一,也是美国首都华盛顿特区声誉最高的综合性私立大学。它位于首都华盛顿地区市中心,坐落在风景美丽如画的乔治城以及波多马克河边,距离白宫3200米左右。

该校在全美3000多所大学中,综合排名第23,是美国门槛最高的大学之一,与哈佛、耶鲁、普林斯顿、斯坦福等大学一起被公认为全美最好的大学。

这所大学有“政客乐园”之称,因为美国联邦政府的办公厅就在咫尺之遥,不少外国使节的儿女也都在这儿念大学。由于该大学基本算是一所耶稣会的天主教学府,所以所有学生必须修读两个学期的哲学和神学。校园内神父可以说处处可见,事实上全部低年级的宿舍,每层楼都有一名神父,担任舍监或辅导工作。不过,神父们从来不会主动向你传教,但当学生需要时,他们肯定会竭诚帮忙。

该文作者Deborah Tannen是乔治敦大学著名的语言学教授,著有You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation,该书已被翻译成29种语言,在世界各地畅销。