这是一个“危机”无处不在的时代。经济危机的“阴霾”尚未完全消散,就业、生活等种种压力引发的“精神危机”亦日渐凸显。从“三聚氰胺”事件引发的针对食品安全的大众信任危机,到富士康多起员工自杀事件背后隐藏的个人心理危机,我们不难看出:“精神危机”已经潜伏多时,只不过我们往往忽略了它的存在,以致其突然来袭时,我们茫然失措,不知心安何处。相比经济危机那可量化的巨大损失,“精神危机”导致的后果更为严重且影响更为深远。在这期主题里,让我们一起来探讨下“精神危机”这个不算新鲜但耐人寻味的话题。

这是一个“危机”无处不在的时代。经济危机的“阴霾”尚未完全消散,就业、生活等种种压力引发的“精神危机”亦日渐凸显。从“三聚氰胺”事件引发的针对食品安全的大众信任危机,到富士康多起员工自杀事件背后隐藏的个人心理危机,我们不难看出:“精神危机”已经潜伏多时,只不过我们往往忽略了它的存在,以致其突然来袭时,我们茫然失措,不知心安何处。相比经济危机那可量化的巨大损失,“精神危机”导致的后果更为严重且影响更为深远。在这期主题里,让我们一起来探讨下“精神危机”这个不算新鲜但耐人寻味的话题。

诚然,探讨“精神危机”的目的不是想让大家忧心忡忡,陷入慌乱之中,而是提醒大家予以重视并寻求应对解决之道。“危机”言下之意即“危险与机遇并存”,唯有直面“精神危机”,我们才有可能寻求更多改变,进而转“危”为“机”,化危为安! ——Maisie

文字难度:★★☆

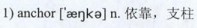

Grateful” was a word that annoyed me all the way through my childhood and I vowed, “I don’t need to hear it again.” But I have to use it to justify how I feel today. I don’t ever want to forget that it was my two children who became my1)anchors in times of sadness, suicidal tendencies, rejection, and identity crisis. That is why it is fundamental that I don’t get myself absolutely lost in the emotions of my losses.

在我的整个童年生涯中,“心怀感激”这个词都让我不胜其烦,于是我发誓说:“从此以后我再也不要听到这个词了。”可是今天我却必须要用它来表达我的心情。我永远都不想忘记,当我陷入忧伤、有自杀倾向、自暴自弃和遭遇身份认同危机时,我的两个孩子成了我的精神支柱。这也是为什么我并没有因为我所失去的一切而完全迷失自己的最重要原因。

I have lived my life with shame, anger, low self-esteem, and no confidence. But worst of all has been living my life without knowing who I really am. This is something that most people know. You may ask why I don’t; I am a fair-skinned, 2)aboriginal person who happened to be born at a time when the governments determined it was best for me to be removed from my parents, and my culture. And I was 3)brainwashed into believing I was an orphan.

一直以来,我羞愧、愤怒、自卑、没信心。然而最糟糕的是,活那么久,我却一直弄不清楚自己究竟是谁,而这对大多数人来说都是再明白不过的了。你可能会问,为什么我会弄不清楚呢?那是因为我是一个浅肤色的澳洲土著人,却正好生不逢时——当时的政府决定将我带离我的父母和我的文化,认为这对我来说是最好的选择。接着我就被洗脑了,一直相信自己是个孤儿。

I haven’t had a lot of 4)socialising at all with aboriginal people—I feel they are not the same as me in their way of thinking. I believe some think I am a “coconut,” which means you are dark on the outside and white on the inside. Another reason has been my denial and identity crisis: I cannot openly say, “Yes, I am an aboriginal person.” Throughout my childhood, my upbringing in a white society taught me to have this type of attitude as a fairer child, regardless of my 5)aboriginality. This was the English 6)teaching that was introduced to enable fair-skinned aboriginal people to forget their identity and forget about their own families. It doesn’t mean that we classify ourselves as being any different; it’s what we were taught to believe as children. Now when anyone asks me where I come from, I just say “Australia”, and leave it at that.

我的生活与澳洲土著人的生活并无太多交集——我觉得他们的思维方式和我的不同。我相信有些人认为我是个“椰子人”,说我外“黑”内“白”。另一个原因是我否认自己的土著身份,陷入了身份认同危机中:我无法公开承认“是的,我是个土著人。”在我的整个童年期间,我在白人社会中被教养成人,他们教导给我的观点是——尽管我有着土著人的血统,我依然是个浅肤色孩子。这就是加诸我们身上的英式教导,让我们这些浅肤色的土著人忘记自己的身份,忘记自己的家族。但这并不意味着我们自认为与众不同,只不过我们从小被教育去相信自己与众不同罢了。如今,当有人问我来自哪里时,我只说“澳大利亚”,不再多说。

In 1905 an act was passed to 7)make provision for the better protection and care of the aboriginal inhabitants of Western Australia. Later, in 1936, another act was passed in which Mr. A.O. Neville, the Chief Protector of Aborigines, was made the legal guardian of all aboriginal children. This act has affected my life, because I was born in 1942.

1905年,一项有关为西澳大利亚土著居民提供更好的保护和照顾的法案通过了。后来,在1936年,当局又通过了另一项法案,在该法案中,土著居民的主要保护者A·O·内维尔先生成为了所有土著儿童的法定监护人。这项法案影响了我的人生,因为我出生于1942年。

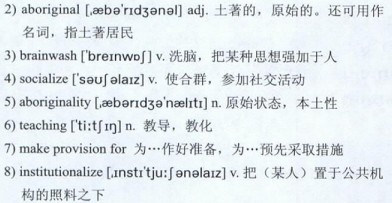

Under this act I was 8)institutionalized for eighteen years. The memories of my childhood are empty, with 9)stubborn scars10)embossed on my heart that cannot be erased. Institutionalisation experiences can be11)traumatic for most children, 12)irrespective of what colour they are. However, for fair-skinned aboriginal people, their identity, culture, and family unity are stripped from them as they are prevented from associating with darker-skinned people.

因为这项法案,我被收容在孤儿院中度过了18年。我的童年记忆是一片空白,心中那难以愈合的伤痕总也挥之不去。在孤儿院成长的经历对于大多数孩子来 说——无论他们是什么肤色的——都是段痛苦记忆。可是对于浅肤色的土著人来说,由于他们被阻止与深肤色的人交往,因此他们的身份、文化和家庭的统一性都被剥夺了。

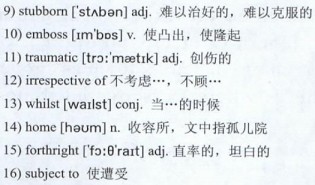

13)Whilst living in the14)home we were informed that we had no parents: “That is the reason why you are here in the orphanage.” We were also told we must be “grateful” that we had “someone to care for us” there. I’m not too sure what they meant about “caring”, but I certainly don’t recall being cared for. To be 15)forthright, I believe we were 16)subjected to abuse, mental trauma, and rejection in all ways—so this is the form of caring we were given. They said this was being done “in the best interest of the child,” that it was important that the children were raised according to white Australian standards. Did anyone bother to ask us in later life whether this was the best policy? Absolutely not. Children who were taken forcibly by the government were herded like 17)cattle. However, how does one deal with these sorts of memories and the emotions they bring up? You can’t reason with this kind of behaviour and it definitely leaves you wondering how you cope without living in denial. Sometimes, the hate inside is unbearable, as you think, “Why couldn’t I be like any other person?”

住在孤儿院时,我们都被告知,我们是没有父母的:“这就是为什么你们在这孤儿院里的原因。”我们还被告知,我们必须要“心怀感激”,因为在那里“有人照顾我们”。我不太清楚他们所说的“照顾”是什么意思,但可以肯定的是我没觉得受到过照顾。坦白说,我认为我们在各方面都受到了虐待、精神创伤和排斥,这就是给予我们的所谓“照顾”了。他们说,这一切都是“为了孩子的最大利益”,要根据澳洲白人的标准来抚养孩子,这点是很重要的。可是,是否有人费心问过我们这些人后来的生活,来以此判断这项政策是否是最好的?完全没有!孩子们被政府强行带走后,就像牲口一样被养大。但是,当这些人长大以后,他们该如何去应对成长过程中的这段记忆和那些情绪呢?你无法解释这种行为,而它肯定会让你有所疑惑:如果不想余生都活在否认自我身份的阴影下,该怎么办。有时候内心的憎恶让人难以忍受,因为你会想:“我为什么不能和其他人一样生活呢?”

Although we cannot change things that have happened, a journey of healing has to take place. This did not begin for me until I was 47 years old. It is an ongoing struggle of unearthing information, which through the years has 18)taken its toll in many different ways.

虽然我们无法改变已经发生了的事情,但开始一趟“疗伤之旅”却是十分必要的。直到我47岁那年,我才开始了“疗伤之旅”。这是一个不断发掘未知信息的艰难抗争过程,在过去的这些年里,它在许多方面都让我付出了无数的代价。

My first step was in 1988 when I decided to search for my government papers, which I received from Community Services in Western Australia. This was the most unexplainable feeling, to see such documents written about me and my life as a two-year-old, and to know that I was the subject of that policy of separating pale-skinned children from their parents. Until then I had been unaware of all the things that went on in those years. Through my government papers, I was able to find out where I was born and where I’d lived for the first two years of my life. The papers also gave me an insight into the type of person I was.

1988年,当我决定搜寻当年西澳大利亚社区服务机构给我发来的政府文件时,我迈出了第一步。当我读着这些关于两岁时的我及我的生活的文件,知道自己是将浅肤色孩子与其父母隔离的政策的对象时,那是一种最难以解释的感觉。在那以前,我一直都不知道那些年来所发生的一切。通过阅读这些有关我身份的文件,我终于知道了我的出生地及我在两岁前居住过的地方。这些文件也让我了解到我的真实身份——土著人。

People—whether non-aboriginal or aboriginal—who have been raised with family and lived in their own culture are able to have a 19)sound knowledge of their past and present situations. For most Australian Aborigines, having been denied the experience, gaining this knowledge generally means taking a trip to the library in search of what are known as “government papers”. This is where I discovered things about myself.

那些由家人抚养长大且生活在自己的文化氛围中的人们——无论是非土著居民还是土著居民——都能够对自己过去和现在的情况有着全面的认知。对于大多数被剥夺这种体验的澳洲土著人来说,获得这方面的认知大概意味着要前往图书馆搜寻那些被称为“政府文件”的东西。而就是在那里,我发现了关于我自己的东西。