看到这篇文章时,恰逢我国西南地区遭遇严重旱情。看着那一片片干涸开裂的土地,那一双双渴望甘霖的眼睛,我不由地想起了那句流传盛广的广告词:“如果人类不从现在节约水源,保护环境,人类看到的最后一滴水将是自己的眼泪!”这个形象贴切的比喻时刻警示我们:水是生命之源!如果我们认为地球无限慷慨,因此就可以大肆透支水资源的话,终有一天我们将会欲哭无“泪”!这不是危言耸听,而是当前的危急形势已经刻不容缓!地球早已发出干渴的喊声,我们必须立即行动起来,从自己身边的点滴小事做起,节约每一滴水!因为珍惜水,也就是珍惜生命! ——Maisie

文字难度:★★★☆

We keep an eye out for wonders, my daughter and I, every morning as we walk down our farm lane to meet the school bus. And wherever we find them, they reflect the magic of water: a spider web drooping with dew like a 1)rhinestone necklace, a rain-colored 2)heron rising from the creek bank. One astonishing morning, we had a visitation of frogs. Dozens of them 3)hurtled up from the grass ahead of our feet, 4)launching themselves, white-bellied, in bouncing arcs, as if we’d 5)been caught in a downpour of 6)amphibians. It seemed to mark the dawning of some new 7)aqueous age.

每天早晨,我都要陪我女儿穿过农场小路去等校车。我们每天都留心观察身边奇妙的世界,让我们惊喜不已的是处处显现着水的魔力:挂在下垂蜘蛛网上的露珠,好像一串人造钻石项链;一只蓝灰色的苍鹭扑腾着翅膀从小溪边飞起来。有一天早晨,我们还意外地遇到一群青蛙,它们从我们前方的草地里窜出来,然后跳进水里,那一个个白色的肚皮在空中划出一道道弧线,就好像是一阵“青蛙雨”下到了水里。这似乎标志着某个新的“水时代”即将来临。

Before we came to southern 8)Appalachia, we lived for years in 9)Arizona, where a permanent 10)runnel would 11)merit a nature preserve. In the Grand Canyon State, every license plate reminded us that water changes the face of the land, splitting open rock desert like a peach, leaving mile-deep 12)gashes of infinite 13)hue. Cities there function like space stations, importing every ounce of fresh water from distant rivers or 14)fossil15)aquifers. Water is life. It makes up two-thirds of our bodies, just like the map of the world.

在搬去阿巴拉契亚南部之前,我们在亚利桑那州生活过几年,那里有一条流淌不息的小河,对保护当地的自然环境有益。在“大峡谷州”(亚利桑那州的别称),每一个车牌都在提醒我们,水改变了大地的面貌,它像分开一个桃子似的把岩石荒漠分开,留下各种各样深达数英里的裂缝。那里的城市就像一个个空间站,收集来自遥远的河流或者地下水层中每一盎司的淡水。水即是生命。我们身体里有三分之二是水,这跟我们从地图上看到的世界是一样的。

Even while we take Mother Water for granted, humans understand in our bones that she is the boss. Our deepest dread is the threat of having too little moisture—or too much. We’ve lately raised the Earth’s average temperature by 0.74°C, a number that sounds 16)inconsequential. But these words do not: flood, drought, hurricane, rising sea levels, bursting 17)levees. Water is the visible face of climate and, therefore, climate change. Shifting rain patterns flood some regions and dry up others. After enough repetitions of shocking weather, we can’t remain indefinitely shocked.

A world away from my damp hollow, the 18)Bajo Piura Valley is a great 19)bowl of the driest sands I’ve ever gotten in my shoes. Between January and March it might get close to an inch of rain, depending on the whims of 20)El Niño, my driver explained as we bumped over the dry bed, “but in some years, nothing at all.” For hours we passed through white-21)crusted fields and then into eye-burning valleys. And remarkably, some scattered families of 22)Homo sapiens. What brought me there, as a journalist, was an innovative reforestation project. Peruvian 23)conservationists, partnered with the NGO 24)Heifer International, were guiding the population into herding goats, which eat the protein-rich pods of the native 25)mesquite and disperse its seeds over the desert. In the shade of a stick shelter, a young mother set her26)dented pot on a 27)dung-fed fire and showed how she 28)curdles goat’s milk into white cheese. But milking goats is hard to work into her schedule when she, and every other woman she knows, must walk about eight hours a day to collect water.

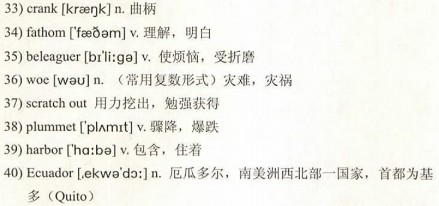

Their husbands were digging a well nearby. They worked with hand trowels, a 29)plywood 30)form for 31)lining the 32)shaft with concrete, inch by inch, and a sturdy hand-built 33)crank for lowering a man to the bottom and sending up buckets of sand. I could not 34)fathom this kind of perseverance and wondered how long these35)beleaguered people would last before they’d had enough of their water 36)woes and moved somewhere else. Five years later they are still bringing up dry sand, 37)scratching out their fate as a microcosm of life on this planet. Civilization has thought the Earth is infinite generosity. Declining to look for evidence to the contrary, we just knew it was there. We pumped aquifers and diverted rivers, trusting the twin lucky stars of unrestrained human expansion and endless supply. Now water tables 38)plummet in countries 39)harboring half the world’s population. Rather grandly, we have overdrawn our accounts.

即使我们认为“水孕育人类”这个事实是理所当然的,但是人类也打心底里很清楚,水还向我们“发号施令”。干旱或水灾都是令我们最为恐惧的威胁。近年来,我们使得全球平均气温上升了0.74°C,这个数字听起来好像无关紧要,但是下面这些文字就不一样了:水灾、旱灾、飓风、海平面上升、决堤。水是气候鲜活的“表情”,气候变化往往通过水来表现。雨量的变化让一些地方发洪水,却让另一些地方干旱缺水。在被灾害天气多次“意外”侵袭以后,我们不能永远保持一副“难以置信”的样子。

跟我家那片潮湿山谷截然不同的是巴霍皮乌拉山谷,它是我曾涉足的最干燥的沙漠盆地。从一月到三月,这里大约会有将近1英寸的降雨量,而这还要取决于是否受到厄尔尼诺现象的影响。当我们驱车颠簸在那干掉的河床上时,司机告诉我:“有些年份,这里一滴水都没有。”几个小时的时间里,我们穿过一片片干硬发白的荒地,然后进入了一片光线刺眼的山谷。值得注意的是,有几户人家散住在这里。作为一名记者,我被吸引过来的原因是这里正在进行一项新的造林计划。来自秘鲁的一些自然资源保护者联合一个叫做“国际小母牛”的非政府组织正在指导这里的居民放牧山羊。这些山羊的主要食物是当地一种富含蛋白质的牡豆树,而且它们会把这些牡豆树的种子散播到沙漠上去。在一个用树枝搭起的帐篷里,一位年轻的母亲用干燥的粪便生起火,架起一个凹凸不平的水壶,然后向我演示如何用羊奶做出白白的奶酪。不过她很难找出时间来挤羊奶,因为像她们这样的妇女每天都必须要走大概8个小时去打水。

她们的丈夫正在附近打井。他们手拿泥铲铲土,然后循序渐进地用胶合板模板来向井筒填充混凝土,接着借助一个坚固的手工曲柄把人送到洞底,然后把一桶一桶的沙子运送出来。我无法理解他们的这份坚定的决心,也不知道这些备受折磨的人们能坚持多久才会向“水困”低头而搬到其他地方去。五年过去了,他们还在挖,可惜只能挖出干燥的沙子。他们的命运就是这个星球上生命的缩影。人类文明总认为地球是无限慷慨的。甚至因为这些成见,人们无视一些很明显的反面的事实。我们从地下抽取水资源,给河流改道,还心存侥幸地相信我们能无限地扩张,资源供给则无穷无尽。现在,全球近半人口所在的多个国家的地下水位都急剧下降,而我们还在大肆地透支水资源。

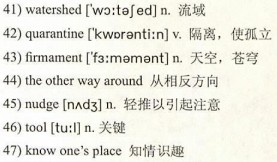

In 1968 the ecologist Garrett Hardin wrote a paper called The Tragedy of the Commons, required reading for biology students ever since. It addresses the problems that can be solved only by “a change in human values or ideas of morality” in situations where rational pursuit of individual self-interest leads to collective ruin. Agreeing to self-imposed limits instead, unthinkable at first, will become the right thing to do. Water is the ultimate commons. Watercourses once seemed boundless, and the notion of protecting water was as silly as bottling it. Now 40)Ecuador has become the first nation on Earth to put the rights of nature in its constitution so that rivers and forests are not simply property but maintain their own right to flourish. Under these laws a citizen might file suit on behalf of an injured 41)watershed, recognizing that its health is crucial to the common good. Other nations may follow Ecuador’s lead.

On my desk, a glass of water has caught the afternoon light, and I’m still looking for wonders. Who owns this water? How can I call it mine when its fate is to run through rivers and living bodies, so many already and so many more to come? It is an ancient, dazzling relic, temporarily 42)quarantined here in my glass, waiting to return to its kind, waiting to move a mountain. Our trust in Earth’s infinite generosity was half right, as every raindrop will run to the ocean, and the ocean will rise into the 43)firmament. And half wrong, because we are not important to water. It’s 44)the other way around. Our task is to work out reasonable ways to survive inside its boundaries. We’d be wise to fix our sights on some new stars. The gentle 45)nudge of evidence, the guidance of science, and a heart for protecting the commons: These are the 46)tools of a new century. Taking a wide-eyed look at a watery planet is our way of knowing the stakes, the better to 47)know our place.

1968年,生态学家加勒特·哈丁写了一篇文章,叫做《公共悲剧》,自此它成为生物学专业学生的指定必读文章。里面讲的是,人类对个体利益的理性追求而导致集体性毁灭的各种威胁,只有在“改变人类的价值观或者道德观念”的前提下,问题才能得以解决。如果人们能自我约束,尽管起初看似不可思议,但那将会是正确之举。水资源终究是人们共有的。曾经,人们认为水道似乎是无边无际的,没有人会去保护水资源,因为那就像要把水一瓶一瓶装起来一样愚蠢可笑。如今,厄瓜多尔成为地球上第一个把“自然权利”写进宪法的国家,他们认为河流和森林不仅仅是一种财富,它们还有权利维持自己的“成长繁衍”。在这些法律体系下,公民意识到该流域水资源的状态对公众利益有着莫大的影响,且可以代表某段受到破坏的流域提出起诉。其他一些国家可以仿效厄瓜多尔的做法。

我的桌上有一杯水,在午后的阳光下显得晶莹剔透,我仍在寻觅奇迹。谁拥有这杯水?这杯水曾经流经了无数的河流和生物体,多少已然,多少未尽,我怎能说它是属于我的?它是一份古老而耀眼的瑰宝,只不过这会儿暂时被抽离存留在我的杯子里而已,它在等待着恢复“原貌”,开山挪土。我们认为地球无限慷慨,这句话有一半是对的,因为每一滴雨水都会汇入海洋,而海洋里的水又会通过蒸发回到天空中。但是这句话又有一半是错的,因为对水来说,人并不重要。这与人们的想法刚好相反。我们的任务是在地球能够容忍的界限内找出合理的方法来求得生存。寻找一些可供人类生存的新的星球,不失为我们的明智选择。但是对我们来说,能让人类迎来新世纪的关键在于:关注各种危险迹象,以科学为指导来解决问题,同时怀有一颗保护共同家园的心。广泛关注我们的星球只是我们知晓其中利害关系的一种方式,更重要的在于我们要明白自己的处境和职责。